|

5. Military Training. Royal Military Police 1.

Monday

came. By now I was used to becoming instantly awake as I heard the Duty

Sergeant shouting reveille in the other rooms before he had entered

ours. I knew that I had to be up. It was useless prolonging a lie in

bed for just a few more seconds.

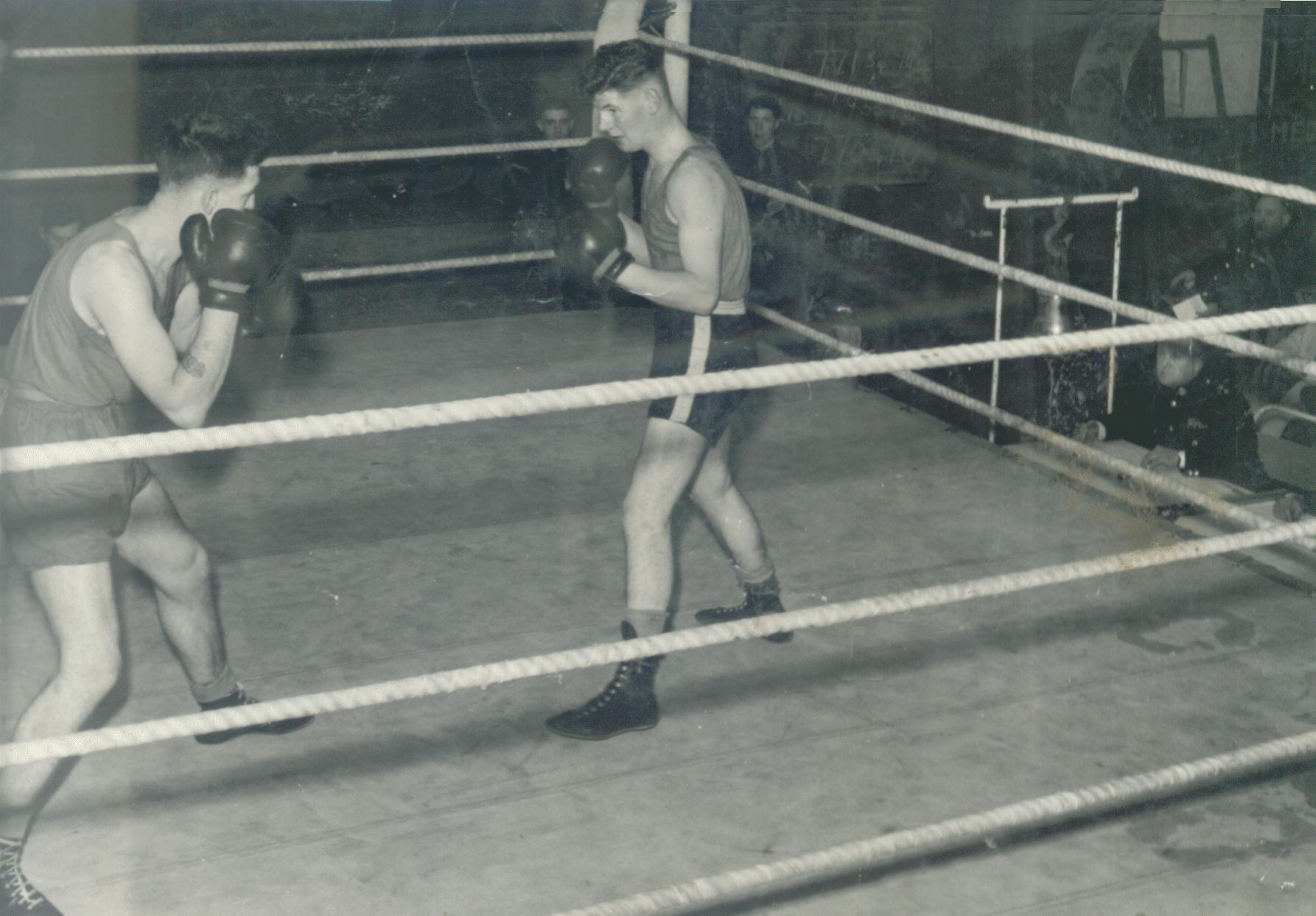

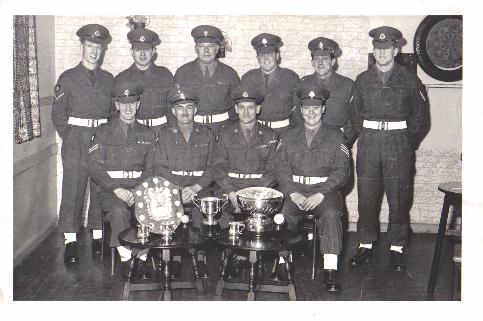

Ablutions. Get dressed. Make bed. Breakfast. Clean bed space. Barrack room duty. Check dress. Be stood at my bed by 7.30 when the Sergeant comes in. Where has all the time gone? There just isn't enough time to do it all. I seem to have just started getting ready and the Sergeant walks through the door. "Stand by your beds" Someone called. I stood there at attention, or what I perceived to be at attention, wondering what was going to happen next. Sgt Friend began to walk up the centre space, stopping, in turn, at each soldiers bed. Picking on everything and everybody. According to him we had wasted the previous weekend. Obviously, to him, we had done no work to our kit or the barrack room. At this rate the squad will not pass out of this depot. I, and I am sure everyone else, was crestfallen. We had all worked so very hard. From the last Friday until now we had been working. Stopping only for Meals, short NAAFI breaks and sleep. I had never worked so concentrating hard and long before. Now here was a Sergeant telling us, me, that I had been wasting my time. I hadn't expected any praise from him but I certainly hadn't expected his berating. He was not satisfied, unless the barrack room was cleaned properly for tomorrow morning the whole squad would suffer. I palled, what more can I do? "Now get outside in Three ranks." He yelled. A mad dash was made by all to get out of the room and not be last. As before we were marched up to the square for Muster Parade. Again we remained at the rear when all the orders were given. As each order was given by the RSM. Sgt Friend relayed to us what was happening. Tomorrow we would be expected to march on parade correctly. When morning muster was over our squad remained on the square. Our first training proper was to be two periods of drill. Most of us had never done drill, or square bashing as it is called. Some took to it quite easy. I did not, I had to work very hard at it and was just about average. Some others were not so lucky. Even standing properly to attention has to be learned. To begin with one tends to try too hard and become rigid. It then looks false and unnatural. The idea is to try and relax but at the same time remain looking perfectly upright. We have all seen guardsmen fall down on TV when they have been standing to attention for long periods. They do so because blood pressure falls due to lack of proper blood circulation to the brain. The trick is to try and relax as much as possible, to curl and uncurl your toes in your boots and to do the same with your fingers. Relaxing and tensing muscle groups also helps. All these movements are acceptable providing they do not show movement. Even marching and keeping in step with others does not come naturally. Prob. Lock could not swing his arms correctly. As the left leg is striding forward, the right arm should swing forward, opposite arm opposite leg. Lock was swinging same arm same leg. No amount of coaching could get him to swing his arms in the prescribed manner. Sgt Friend really laid into him. To hear the sergeant talk Lock was the lowest form of life, he was still a baby who had not yet learned to walk properly., If he didn't learn pretty soon, a nappy and dummy would be fetched and Lock would have to wear them. I'm sure Prob. Lock believed, at the time that Sgt Friend could and surely would carry out his threat. But no amount of bollockings or cajoling could get Lock to march correctly. The sergeant had an idea. He fell the rest of us out for a smoke break. We mustered in the ground floor passage way that surrounded the buildings overlooking the square and looked out of the windows. The sergeant placed Prob. Lock between 2 other recruits who could march. The 3 were in single file facing forward. They were given 2 sweeping brush handles to hold, one on either side. Three right hands were holding one handle with the 3 lefts holding the other. Instructed that on the command "Quick March" They would all begin to march normally swinging their arms. Prob. Lock was told to keep in step with his feet and allow his arms to relax and to follow the directions of the handles with his hands. "Quick march." ordered the Sergeant. Immediately they began to march forward swinging the brush handles with their arms. They started of okay but soon there was much confusion, instead of Lock being taught to swing correctly the others began to swing the same as Lock, same arm same leg. Experiment a total failure. The rest of the squad was in hysterics. It was the funniest thing that I had seen since I had arrived here. I thought that I had forgotten how to laugh up, up to now there had been nothing to laugh at. It took many drill periods before Lock could march properly but perseverance paid off, soon he was as good as anyone else. The first lecture that afternoon gave us a brief history of the Military Police being made a Corps in 1946 the role of the RMP., are soldiers who exercise police related functions in the Army and generally maintain Military Law and order, discover, investigate and prevent crime. That first training day I received my first letter from Brenda. Reading it left me more down than I had already been. She wrote how lonely she was, my son was forever crying for me, all the lights had blown that evening of writing, it turned out to be an only an electric fuse but she had not known how to mend it. I felt wretched. Things were not going according to plan. I had not foreseen all this. When I got the chance that evening I replied to her letter. In it I again tried to reassure her that all would eventually be resolved although whether I believed it myself I had doubts. The Sixteen weeks, I explained, would soon be over. When I passed out of this place and had been posted to an RMP company, I would be able to get married quarters for us all. We would be a united family again. Patience was the key word for us both. I certainly was not on a bed of roses here. That night I resolved to try harder. Tomorrow our Sergeant would have no cause to pick on me. The coming day was to be our first muster parade proper. The next morning came all too soon, before I seemed to have time to turn around we were on parade. This time we marched out with the other squads. We all counted the paces forward in our heads. When we came to the seventeenth we came to a controlled halt. We tried so hard but it was very ragged, all stopping at slightly different times. The RSM bellowed out to us. "Get it together." Then the order came "Open order. March." This in effect means that the centre rank stands still, the front rank moves forward 2 paces, the rear rank moves back 2 It is designed to give the inspecting officer plenty of room to walk between the ranks inspecting the troops. Our squad officer, we learned his name was Second Lieutenant Boyce. He looked a right mummies boy to me. Later I was to find that he played rugby union for the army team and was considered quite a 'hard' man. He certainly did not look it. Lt. Boyce began to inspect us. He looked at each one of us in turn remarking points to Sgt. Friend who noted them in a small book. At the end of the parade, we again remained on the square for a further 2 periods of drill. This time the Sergeant re-inspected us bringing out the points that the officer had noted. On coming to me he said "Have you had a shave this Morning?" On receiving an affirmative reply he said, "then stand closer to the razor next time. I see I am going to have to watch you." He went to town on us all. I ended up thinking I was not worth the ink that was printed on my birth certificate. Although to hear him talk I wouldn't have a birth certificate I was too low a life to have been born normally. All the instructors carried a drill stick. It was a Yard long highly polished wooden rod. It had a silver topped handle at one end with a ferrule at the other. One time Sgt. Friend had inspected me and because I was not up to his requirements he pointed the drill stick end to the edge of my nose and threatened. "If you do not get a grip of yourself, Gale I will push this drill stick up your Right nostril and throw you over my Left shoulder. Do you understand? "Yes Sergeant." I shuddered. And at the time I really thought he could carry out his threat. I was by no means small in stature but he seemed to me a mountain of a man. In later years I was to realise different. What do I have to do to please the man I thought. I really tried hard last night, what more can I do? My only consolation was that everyone in the squad was put through the same ringer before being hung out to dry. That all very well for them I thought, but the Sergeant really means it when he gets on to me. That evening Peter and I decided to go for an evening NAAFI break. The NAAFI was situated in one of the buildings that lined the square. We left the barrack room, walked the 100 or so yards and entered the main block passageway. We exited a door of the block that led on to the square area. It was then required to walk at a very brisk pace, arms swinging shoulder high, round the pathway that surrounded the parade ground to the NAAFI doorway. As we were marching, my foot accidentally touched the square at the corner angle rather than the walkway. Instantly a voice bellowed out from across the Square. "Get off my square that man." It was the RSM. No one was allowed to touch, what he called, 'his square' unless doing drills or parades. "Come here. Now." he further shouted. As either of us did not know to whom he was referring to. Both of us doubled over to him. We all stood trembling to attention. the RSM was a very imposing person. His uniform was always immaculate in every way. "No one walks on my square unless I personally give him my permission." He bellowed. He then went into a tirade about what he ought to do with us. I do not exactly remember what because I had visions of spending the night in the guardroom cells. "Walk on my square once again and your feet won't touch the ground when I throw you into the nick. It will be mind your fingers as I clang the cell door shut. Now get out of my sight and don't come into it again. I will remember you both in the future. No go!" We fled away. All I had done was accidentally touch his beloved square. I made sure I never went near it again. The following morning. "Stand by your beds" came the order. We stood. In walked the Sergeant. At the foot of the beds was a small foot locker This had a shelf that displayed our best boots. Every spare minute I would put another thin layer of polish on them. It is called 'Bulling' your boots. Even the arch under soles have to be bulled. The only way to highly polish boots it to continually put thin layer after layer of polish on them. With a duster covered index finger using round circular movements you worked the polish into the boot. Occasionally spitting on the boot or using iced water helped to contain and deepen the shine. The second pair are working boots and only the heel sides and toecaps are bulled, the rest of the boot is brush polished. New boots are not smooth on issue. They have a raised bubbly orange peel effect. This surface has to be honed and smoothed out. The ex. boy soldier showed us how to do it. A thick layer of polish is first applied and the handle of a spoon is heated over a candle flame, it is then honed all over, hours can, and are, spent on each boot. Someone who knew the ropes and had known what to expect produced an electric soldering iron with a blunt tipped end. It did the job of smoothing the leather bubble effect superbly. We were warned not to let any senior rank know of this easier way of honing boots. The old fashioned method was the only way to do it in training. On top of the foot locker were neatly arranged a knife, folk and spoon with your upturned pint mug was placed in the centre. After inspecting the barrack room for minute traces of dust or dirt, and always finding some, the Sergeant descended on the state of the mugs. He gave the order to "Upturn mugs." Going to the first mug in the room he inspected it. He proclaimed that it was dirty, hooked the end of his drill stick into the handle and cast it over his shoulder. It smashed to pieces in the centre of the floor. All along the line he inspected mugs and more often than not found them at fault and hooked them over his shoulder. All fell to the floor and broke. He came to my mug. It was dirty. Again he hooked it over his shoulder but it's trajectory threatened a recruits head who saved himself injury with a reflex action by catching it, consequently there was no noise of it smashing. The Sergeant slowly turned round and looked at the recruit who was holding the mug. No word was spoken but the look from Sgt. Friende froze him. He released the mug and it smashed to the floor. Out of 22 mugs, he had broken 15. They would have to be replaced at lunch time from the Quarter Masters Stores at a cost, to us, of One Shilling and Three pence. (7p) "Fall in outside in 3 ranks. Last one moving gets 20." He ordered. As we ran down the centre aisle to get outside and not be the last in line, we could not help but grind the shards of pottery into our lovingly polished lino. The floor would have to be scoured of polish and resurfaced again that coming evening. A recruits work is never done. Another gruelling day ahead of us. That day we learned about the difference between officers and other ranks. Officers are soldiers who having been selected for officer training and having successfully completed it are then commissioned by the head of the armed forces, this of course being Her Majesty the Queen. Rank begins for them, in the army, as a Second Lieutenant, denoted by a badge of rank known as a single 'pip'. An Officers rank is usually is worn on his shoulder epaulette. They are always addressed as 'Sir'. Other soldiers start at the lowest rank of private, or in our case probationer. The first promotion by one stripe is to Lance Corporal he is then a 'non-commissioned' officer, an NCO. All NCO’s are usually addressed with their rank. The highest NCO rank is a Warrant Officer First Class. All WO's are addressed as sir. The highest warrant officer at our depot was the RSM. On the drill square we were being shown how to salute. Sgt. Friende ordered every one to a position of attention and then to salute. He walked down the ranks correctly positioning our right hands. The fingers had to be outstretched with the index finger touching the right eyebrow. The palm was flat outward and the elbow held high. It was a cold day and we were wearing Karki woollen gloves. Peter had half his right ring finger missing due to the mining accident earlier described. As Sgt. Friend moved to him he saw the loose gloved finger end hanging down. Grabbing what he thought to be a loose finger he began to yank at it. Bellowing at him, at the same time, as to his slovenliness. He soon realised that there was no finger within the glove. He was so surprised that for a brief moment he was lost for words. "What's this?" he blustered. "Finger off Sergeant." Was the Peter's reply "Well get the glove sewn up sharpish." Was all he could think of to say. "Today you are going to shed blood for your country, literally." The Squad Sergeant, one morning, announced. "You are all going to volunteer to donate blood. Do I make myself understood? You will have to volunteer" The emphasis on the word 'will' left no one in any doubt as to exactly what he meant. "This squad has been specially chosen to give blood to the Royal Army Medical Corps. RAMC. It is purely voluntary and you will be required to sign giving your permission. This blood helps those that may sometime need it. It could be you tomorrow. And if you don't buck your ideas up in training it may well possibly be one of you that may need it." "All those who have decided to donate blood outside in 3 ranks. The remainder stay put, I'll think of something for you to do to keep you occupied." To a man everyone formed up outside the barrack room. I was quite willing to donate blood, it would be a first time for me. I wondered what the veiled threat contained if any of us had refused. Outside the guardroom an army bus was waiting to take us to the Military Hospital, Aldershot. Having never given blood before and I was a little apprehensive. I shouldn't have bothered it was nothing really. At least it got us out of barracks for the morning. We all received a copy of the training schedule for the coming eight weeks. There were at least 2 periods of drill and 1 of PT, Police holds or the Assault Course per day. Most of the other periods were held in the classroom. Thursdays was pay day. At certain times of that day each squad would parade outside the orderly room in single file and in alphabetical order. Inside the room would be a trestle table, behind which sat an officer and the pay Sergeant. Your name was called, you came up to attention and marched smartly into the room, halt at the table and salute the officer. The pay Sergeant would hand the officer your pay book and a certain amount of money. With your left hand you would take your book and money. Salute the officer and state. "Pay and pay book correct, Sir." About turn and march out. Outside you could then inspect your pay book details to see if in fact your pay and book were correct. Woe betide anybody who inspected his pay book before giving the officer the required answer and salute. I have to say that at no time was my pay and details other than correct. The army can make mistakes but they were not out to cheat you. Mistakes were rectified, unlike the mining industry at times. Each barrack room had a 'drying room' this was a place where centrally heated pipes lined the middle, and walls of the room. When completing the assault course for example we could be wet sodden through. Clothing was hung and dried there. Smalls could be hand washed and dried. Laundry for larger items was handed in, once a week, and returned the following week at no extra cost to a recruit. One sheet and a pillowcase could be exchanged per week. In the classroom part of a lecture was about who to salute. All other ranks (ORs) who are wearing head-dress, are required to salute all officers. If a soldier is indoors and is not wearing a hat he must come to a position of attention as a form of salute. A soldier who is sitting, when an officer enters, should rise and come to a position of attention. We were reminded that when we salute an officer we are saluting the Queens commission, not the person. Most officers I found were worthy of a salute but a few were worth the splitting of the index and second finger for. A soldier in uniform is also required to salute a hearse carrying a coffin, as a sign of respect. At the end of the lecture the instructor asked if there were any questions. One recruit asked what one should do if he was sitting on the upper deck of a bus wearing uniform with hat and a hearse went by. "Look the other way, idiot" replied the Sergeant. We were issued with an identity card which bore the recipients photo. It was embossed with an army stamp and contained the soldiers details. It was AF (Army Form) 2603/4 (The 2604 was the plastic cover container) A soldier is required to have the ID card in his possession at all times. Through my own negligence I lost mine. I searched high and low, all to no avail. I could put off reporting it's loss no longer. The Sgt. went hairless. I was not only lazy, scruffy and an idiot. I was now an incompetent lazy scruffy idiot. He would have to report the loss to the Commanding Officer. I would be on CO’s orders tomorrow morning at nine. That evening I was at my lowest ebb ever It had been instilled in me, the importance of the ID card. A finder, in theory, would be able to enter any British army camp in the world. I had been left in no doubt about the seriousness of my offence. The following morning I paraded outside the Orderly rooms for CO’s orders. I did not know what was to happen when I was ordered to take off my hat and belt. I had previously seen films of soldiers being paraded and their badges of rank and buttons tore from their uniforms. Their sword was broken over a knee. Was this to happen to me? I didn't even have a sword! Two NCO’s in full uniform were to be my escorts. The RSM commanded us to attention. "Left Right, Left Right, Right Wheel, Mark time, Left Right, Left Right, Halt." Came the staccato commands. Before I had realised it I was in the CO’s office. I didn't know whether I was coming or going. Sgt. Friende was called to give evidence of the loss. The OC asked my version of events. He then gave me a lecture on the gravity of my offence and pronounced. "Case admonished" It was a minor reprimand. The RSM then bounced us out in the reverse as he had done in. I was glad to get out. I felt that I had been treated very fairly. I learned a lesson that day from then on I always knew exactly where my 2603/4 identity card was. Slowly but surely we were gradually adapting to training. We did very little work in relation to Police work other that a Military Policeman's role in a Theatre of War. The first Eight weeks we were being trained to become soldiers. On the second half of the course the specialised Police training would be given. Although we wore dark blue berets for the first 8 weeks, all had been issued with a peaked forage hat. The chin strap of the it was new pigskin. It had to be a stained mahogany brown and then given a highly bulled finish. Polishing the chin strap was an art in itself which I quite excelled, mine was as good as any other in the squad. pity my boots were not. The red hat that my mate down the pit had remarked on was not a permanent feature of the forage cap. A cloth elasticised red cover was thoroughly wetted before being placed on the hat. With a pair of tweezers each individual crease had to be tweaked into an exact pattern. It would then dry in that shape. We often placed the covered hat on our heads and pretended we were the real thing. Ah! some day soon. The wearing of the red topped hat and armband signifies that the policeman was on duty. We were instructed that, in theory, the MP is always on duty. Each time I received a letter from home it was in the same vein as the one before, things were not going right at home. The training was hard and at times it seemed too much, it was such a different life from the one I was used to down the pit. When I was down I felt like packing it all in but then I would realise the opportunities that could open on the completion of my training. I knew I had to stick it out to the end. I would dread getting letters from my wife it did not help me at all, after reading them down I would go. At least once a week half of the squad was required to do guard duty. We had to parade, in uniform, for inspection. From six in the evening to six the following morning we were on call in the guardroom. We spent four hours inside and two hours patrolling the barrack grounds outside. The piquet's patrolled in pairs and were each armed with a wooden pick halve. Each pair had a different route around the depot. A solitary guard was positioned outside the guardroom entrance, he gave warnings of any approaching persons. During the four hours inside we had a bunk and mattress, we were allowed to sleep. When not sleeping we had plenty of studying and kit cleaning to do. We could not get undressed in any way. The boots had to be kept on for the full 12 hours. We also had them on for the next coming days training. When one half of the squad was on guard duty the other was on Fire Piquet. This entailed being in a room for twelve hours. We were on duty in case of a fire call out. Theoretically we would be the first on the scene of any discovered fire. Again it was a two on and four off duty but we never left the fire piquet room. It was the evening of the Depot Boxing Tournament. There were four squads in camp all at different stages of training. Ours was the junior squad. Every man in the junior squad has to take part in 'milling'. To describe milling:- An equal number of men form a queue just on the steps at the entrance to two opposite corners of the boxing ring. At the sound of the bell the first pair enter the ring from the facing corners. They then attempt to batter the living daylights out of each other. When the bell sounds again after one minute they quickly get out of the ring being replaced by two others. Milling then begins again. It isn't a boxing match, it is designed to show courage and the 'guts' to have a go. Peter was part of the Milling team. He had never been in a ring let alone boxed before, no matter all he had to do was try. He gave a very good account of himself but unfortunately his ear was nicked, nothing serious but it bled profusely. He came out of the ring looking as if he had been in a massacre rather than a minute of boxing. The other three senior squads had to produce four boxers at differing weights to compete as an inter squad competition. At the exhibition match with Corporal Miller I managed to out point him. After the boxing tournament Captain Thomas congratulated me on my win. He said that I had won quite convincingly. Would I like him to arrange other boxing matches both army and civilian? I said Yes, more because I did not know how to say no to an officer. Also I was wondering how it would affect my training. The Captain said he would put the matter in hand. Training continued, it never seemed to get any easier. The more I learned about Army ways the more I realised how little I knew. We had been in training now for four weeks. Every letter I received from Brenda was in the same vein, Why did I ever have to leave and join up? how unhappy she and my son were, how empty the house was. It made my training twice as hard as it should have been. I on my part knew it would all work out for the best in the long run, time will tell. Every letter I sent, almost every day, tried to reassure her of this fact and always ended with the words, 'I love and cherish our marriage' which summed up my feelings. On the forth Saturday afternoon, as he had been earlier arranged, Captain Thomas picked me up and we drove in Woking. There was to be a local boxing tournament. An opponent had been lined up for me. The upshot was that I beat him quite comfortably. the Captain said he would arrange further matches The days wore on and became weeks. By now we were not the junior squad but the junior intermediates. Certain thing I excelled at like PT, Assault Course, Self Defence, Police Holds. Most other things I was only average, Drill, Army theory and the like. In certain things I was useless or thought I was useless. For instance I could never seem to get the high gloss finish to my boots. to put them aside shoes or boots in civilian life they were immaculate. Put the beside any other recruits boots they were manure. I was tempted to say shit but I have tried to keep swear words out of this account. Although recruit training would make a parson swear. I spent hours, days, no months on my boots but they never seemed to come up to requirements. I blamed everything on my deficiency. The Polish? I was using Kiwi like everyone else. My duster? The others bought them from the NAAFI like mine. The iced water? was I using the wrong type of ice? My spit? that seemed to be the only common denominator. It now seems stupid to blame spit but that's how important it was to me at the time. I tried everything all to no avail. Many was the time that I was threatened by the Squad officer Lt. Boyce that I would have to buck up my ideas or I would not be getting the 3 day pass in 2 weeks time. At that stage I would rather him say that he was to take off my right arm rather than withhold my 72 I needed the leave to try to make things okay with my wife, her letters continually left me in no doubt where she stood in relation to the army. On Saturday of the Sixth week Captain Thomas again picked me up for another boxing tournament in Guildford. When we arrived the organiser said that my intended opponent had rung in sick. We had come all this way for nothing. I was not worried being only too glad to get away from the claustrophobic atmosphere of the camp for a few hours. Just as the tournament was about to begin in the late afternoon, the organiser again came up to the Captain and I. He said that he had another boxer who was without a fight. He was my weight but vastly more experience than I. He had been an ABA finalist twice in a row. Did I want the match? I said of course, but secretly I was a little afraid of the competition. The organiser said that I did not have much of a chance but at least I would get a prize and would not have come all this way for nothing. That cheered me up no end. The bell went for the first round. the other boxer, his exact name escapes me, it was Redland, Redfern or something like that. He was obviously well experienced. Our styles were much alike in many ways. I was an orthodox boxer and my main punch was a straight left with a right counter. He was the same, over time I threw my left he threw his, with the result that we both connected at the same time and I did not get chance to throw my right counter. I was getting good solid punches in but so was he. I felt his were the harder and I should know I was on the receiving end. The fight continued in much the same vein throughout. I knew he had beaten me to the punch consistently. The final bell sounded. We retired to our corners to await the judges verdict. At that time the boxers did not go to the centre of the ring where the referee announces the winner by raising his hand. Then boxers remained in their corners until the winner was declared. It was customary for the winner to go over to the defeated boxer, shake hands, show sportsmanship and utter commiseration's. I knew I had lost, I had been beaten by a better man "Gale in the Red corner the winner." The announcer declared. I realised that a mistake had been made and I waited in my corner for it to be rectified. My opponent remained in his corner, he was expecting me to go over to him. After a short wait he ducked under the ropes and left the ring. Where is he going? I thought, surely he knows of the mistake and that he really had won. I left the ring and someone ushered me to the prize table, I collected a table lamp. When I got back to the dressing room the Captain gave me the rollicking of my life. "How could I have acted so unsportingly? They would never again invite him or his boxers again. I had shown the Corps of the Royal Military Police up." I tried to explain my confusion but it did not seem to gel with him. I left the tournament under a cloud. I didn't like, or want, the table lamp anyway. On the seventh week of training we were taken to the shooting ranges for live weapon firing. MPs are taught to handle and specialise in 3 types of weapon. Rifle, Sub-machine gun and the pistol. We were introduced to the LMG (Light Machine Gun) but only briefly. The long barrelled weapon was either the old 303 rifle or the new SLR (Self Loading Rifle) with its 7.62 mm rounds of ammunition. The sub-machine gun was the 9mm Stirling, SMG for short. The pistol a .38 and could be a Colt, Webley or the like. This was to be the first time I had ever fired a live round. We had been briefed and trained how to handle the weapons with dummy ammunition prior to arrival on the ranges. Sergeant Freedman, who was the RMP armourer informed us that the instructors on the rangers would tend to be a little quieter than usual, not because they had grown soft but because they did not want any recruit being startled whilst holding a weapon containing live rounds. One recruit did inadvertently point his weapon away from the target area whilst enquiring on a point of procedure. The armoured lapsed into a fit of fury. At one time I thought he was about to wrap the rifle barrel around the recruits neck. Even though the weapon was not loaded with live rounds it is still never pointed at anyone. The only time it is, is when it is used for the purpose for which it was designed. At the end of every session on the weapon ranges we had to parade before the officer or senior NCO in charge, showing an unloaded weapon and stating , " I have no live rounds or empty cases in my possession, Sir" At the onset of training we had been issued with 2 sets of webbing. one set of 14 items had been blancoed Karki Green. We wore and used them during the first half of training. The other set were to be white, 9 items. It was known that if any recruit did not pass the eighth week they would be back squadded to the junior squad, four weeks. They would then automatically lose the 72 hour pass. From week nine onwards we would be wearing white webbing with our uniform. The berets would change to the MP forage hat, not with the red cover that would come later. All that weekend our daylight hours, was spent on the whites. First scrubbing them down and then bleaching them in neat bleach. Further scrubbings followed. We applied numerous coats of white blancoe, washing it off then reapplying. Each time all the brasses of the webbing’s had to be cleaned with 'brasso'. It is impossible to exactly relate how hard and diligently we worked our whites, we knew how important they were. We lived and breathed whites that weekend. On Monday morning the whites would have to be displayed in a regular pattern across the bed. Some decided that they would not have enough time between reveille and morning muster. Many laid out their whites that Sunday evening. They slept on the floor covered in a couple of blankets. I and the rest arranged to be awoken at 4.30 am for the preparations. I missed breakfast that morning. Monday morning. The room practically gleamed with the white webbing and shone with the shiny brasses. All were laid very carefully across the bed in an exact orderly fashion. It seemed a glorious sight. It was worth all the hard work we had put into it. We waited nervously for the Sergeants entrance. This was one of the few times that we were fully prepared and standing by our beds before he came in. "Stand by your beds." came the order, quickly followed by "Outside in 3 ranks" We all rushed, to a man, outside to be taken for morning muster. After the parade we returned to the barrack room. "Stand by your beds." We complied. Sgt. Friend then went to the first mans bed. There laid out were the nine items of white webbing. "Is this supposed to be white?" He bellowed. "It looks a mucky shade of grey". He proceeded to the next mans bed making roughly the same type of comments. "Did I, or did I not say that today was to be a whites inspection?" he remonstrated. "How dare you all insult me and my intelligence with this rubbish?" He began marching up and down the room stopping at each in turn utter threats of punishment and promises of withholding the 72 hour pass. He returned to the first mans bed. Looking over it again he scooped up, with his drill stick, 3 offending items of the webbing. Going to the next bed he scooped up another 2 pieces. By the third bed and scooping up 5 pieces he realised that the stick was eventually going to get too heavy. He ordered 2 recruits to get the brush and to hold it at each end. A third was ordered to put indicated items over it. Half way down the room Sgt. Friend said "Oh! I've had enough of this. Put every item of webbing on the brush. When I say a whites inspection that is exactly what I mean. Fall in outside. You two," indicating the two who were holding the broom handle covered webbing. "bring the webbing." We all rushed outside wondering what was going to happen and expecting the worst. He marched the squad round the barrack lines to the boiler house area. The two carrying the webbing bringing up the rear. Situated at the boiler house were huge coke burning furnaces that heated certain areas of the camp. The squad was halted at the side of a large empty coke container. It still contained remnants of coke and coal dust. Throw it in." He commanded the webbing carriers. The webbing was thrown into the skip. "You." Pointing at me. "Get in." I climbed in. "Mark time. Left Right Left..." was the order. I began to march, on the spot, over the white webbing. For a full minute I marked time on the webbing whilst Sgt. Friend berated the squad on their failures. Sergeant friend was no friend of ours. "Halt. Gale, throw it all out. All of you now fall out, retrieve your webbing and fall back in again.". All the items had been stencilled with your own army identity number. We all scrambled, each for his own. "Tomorrow morning there will be a further whites inspection and anyone who does not pass it will not be granted a 72. That is my promise." After returning the webbing to the barrack room we were marched off to lectures. That lunch time we began the procedures all over again for getting the whites ready for the coming morning. The morning came and as before the Sgt. Friend walked up and down the room inspecting each set of whites making individual comments. We were worried because we thought that the general standard was not as good as before. We just had not as much time to spend on it. "It is not a good standard but at this stage it is only just passable," he pronounced. We all breathed a sigh of relief. "Now lets get some work done. Outside in three ranks." All that week we worked like we had never done before. Perhaps, just perhaps I might make the 72 after all. Friday morning Lt. Boyce conducted a pre pass out kit inspection. We were to wear our best BD. (Battledress) Green webbing and Berets. This coming afternoon would be the last time, in normal circumstances, that we would wear green webbing in training. When we returned after our 3 day leave we would begin wearing whites and a peaked hat. It would signify we were trained soldiers and were in further training to become Military Policemen. As Lt. Boyce was inspecting my boots he remarked that unless they were better by this afternoon I would not be passing out. I calculated that I must have put over 400 thin layers of polish on my best boots before I ever wore them for the first time. That was on the eighth week passout. I do not exaggerate on the number. My boots were the best I could get them surely they would not back squad me for the sake of a pair of boots? I believed they would. I arranged for the ex boy soldier to give them a final coat of polish, he had an extraordinary knack of bulling boots. His were even better than the Sergeants if that was possible. When they were returned, without question, they were a lot better and I breathed a sigh of relief. What was his secret I didn't know. Friday afternoon we marched out on to the square. We were inspected by the Commanding Officer who congratulated us on our turnout. We marched up and down the square to our instructors commands and proved that we were truly trained soldiers. It was a minor proud moment for me. Now could I take and pass the second half? Each of us was given a 3 day leave pass and a rail travel warrant. I was the happiest person alive, I was going home. We had been previously warned that until our full passout we could not wear civilian dress, even on leave. But because our 3 day pass was so near Christmas, our squad had been selected for duties over that coming period. On this occasion we would be allowed to bring back some civilian dress for us to wear, when not on duty, over the Christmas period. My leave pass began at 1600 hrs Friday and expired at 2359 hrs Sunday.

Peter

and I travelled together and I was so pleased to reach home. My wife

and son welcomed me with open arms. I now knew what a prisoner feels

like on his release. I had a lot of serious talking and convincing to

do in the coming day or so.

Eventually Brenda and I began to discuss our future. She had her idea of it and I had mine. I could see her point of view, what she wanted was a life with a stable future rather than the uncertainty of the army unknown. I wished she could have been more like Peter's wife Marlene, she only wanted what Peter wanted. My wife's argument was: I had promised that if we did not like the army there was a get out clause in my service contract. It stated that: - In the event of my not being compatible with the service, I had the option that I could obtain my discharge by purchase in the sum of Twenty Pounds, providing that option was take within Twelve weeks of my enlistment. I had to admit I had given her that prior promise. But I had not expected to seriously have to consider this prospect. Brenda urged me to take the option. I had been signed on now Nine weeks. I tried to console her. Once I became fully trained and obtained a posting, we would be reunited in married quarters. Her reply to that was that she was happy enough in her own home she did not want anyone else's. She had further complaint, there was less money coming in now I was in the army. I could not argue with that, I had taken a huge drop in wages when I left the Mining Industry. She urged me to buy myself out and return to the pit. The mere thought of going back down the mines again, after seeing what the army could offer me, filled me with dread. I would never go down the pit again whatever happens. I had a happy, though sad weekend, nothing was resolved and I still did not know in which way I was headed. I returned to barracks. Entering the guardroom, again I was again presented with the very strict regimentation of booking in by the Guard Sergeant. But this time it was different, I knew what the score was, I was aware of the rights and wrongs of the system and I knew what was expected of me. I realised that I had changed. I had become a soldier. Now I wanted to become a Royal Military Policeman. We resumed training but now Sgt. Friende's attitude to us seemed to have changed. He had moved up a gear and so had we. Now we were getting less bollockings, sorry tellings off, about our kit. Just as important I began not to take the criticism to heart but to endeavour to try harder to correct the complaint. The emphasis was now the role of the RMP in the Armed forces. One Friday evening after duties Sgt. Friend came into our barrack room to remind us of something. I remember not what. He told us all to be at ease with him and to gather round. He was not here in his official capacity and seemed quite friendly. I do assure the reader that our Sergeants name was indeed Friend, our squad number was 773. Sgt. Friend explained that the first Eight weeks of training was designed to demean you. To get rid of all the normal ideas of civilian life. To break you down. Any recruit that gave in at this stage, the army did not want anyhow. When a recruit was at his lowest ebb then he could be manipulated into the Army mould. When he was berating us at inspections and on the square, it was not meant personally. That was the tried and tested way of military training. If I had realised these facts before I started training maybe I would not have taken it all quite so much to heart I pondered. We were still the hounded from pillar to post but now we had an insight of what was expected of us. We had a goal that was not too far away. We could look forward to coming out into the light, that we could now see at the end of the tunnel. Weeks Nine to Twelve were to be almost entirely taken up in the class room studying Law, both Military and Civil. We would have to learn, parrot fashion, huge tracts of it. At the end of the law course a written exam would be held. The exam decided if one passed out of training. Weeks Twelve to Fifteen would be Motor Transport Training. MT. Trg. All Military Policemen must have at least one driving licence for a motor cycle or motorcar. Anyone who already held both would be Army re-tested and may be excused MT trg. I had a motor cycle licence so would automatically be trained for a four wheels. During MT Trg. all parades inspections, fire piquet's and guardroom duties are suspended. MT training weeks are the easiest of all. We were all were looking forward to weeks 12 to 15 Week Sixteen was to be a preparatory passing out of training week. That week we would be informed as to our individual postings. At the end of it, Pass out, and three glorious weeks leave. On our return we would begin preparations to travel, each to our own individual military unit. Oh! the thought of Singapore, Hong Cong, Cyprus, Malta Gibraltar, Aden. These were postings that were now within my dreams, even Germany sounded okay to start with. I had never been abroad in my life. I now could look forward to eventually visiting all of the a/m places. We had been told that the RMP operated a rotary system of postings. Every Two years one changed their unit and usually country of posting. Back to reality, I was still only beginning my Ninth week of training. We received our 'Blues'. This Navy Blue uniform was for ceremonial duties and was tailor made to fit the individual. It was a single breasted high necked collar coat, with stay-bright buttons. The uniform has Red piping down the trouser seams and jacket pockets. The hat was a peaked Black banded hat with a red topped crown. When a soldier wears his blues, in whatever regiment, he feels very special. I know I did. I received a message that Lt. Mayhew wanted to see me and that I had to bring with me my swimming kit. He had booked a driver and vehicle to take us to the Army Swimming baths in Aldershot. I was timed over One Hundred yards free style. He did not tell me my time but I could tell that he was impressed. He said that he may be in contact later. Three days after, I had to go see him again. He informed me that the Military Police was to enter a Pentathlon team in the coming Army championships. It was to be held in Four months time. Was I interested? I enquired what the Pentathlon event was. He explained that it consisted of five events:- Swimming, Cross Country Running, Horse riding, Fencing, Shooting. I explained that I had never done any Fencing, Horse Riding or Cross Country Running. His reasoning was that to train a good horse rider or fencer to swim fast would take much too long. I could swim fast and I had proved I was a good shot. I was fit, or I would become fit, enough for the cross country. The Army would teach me the other two arts. Later, he explained, I would be taken out of training and billeted at the Army Horse riding academy, to be equestrian trained. After that I would go to the Army Physical Training school in Aldershot to learn how to fence and at the same time be trained for cross country running fitness. I expressed my fears that I wanted to finish my training first. I desperately wanted my promotion stripe. He assured, as soon as I began Pentathlon training I would be given my stripe. Recruit training for me would be at an end. I saw this as a great opportunity to better things. I felt capable that I could take the challenge and make something out of it. I agreed to go into training. Lt. Mayhew said that within the next few weeks I would be contacted again. I left with thoughts that to do well in the sports arena could take me high. But I still had the nagging problems about my wife. Our Squad was on duty over the Christmas period. Most staff and all other recruits had gone on leave. The squad was be split in half. Each half doing 24 Hours alternately. The half that was not on duty was duty free and could leave camp provided we booked in and out at the guardroom. During the Christmas period there were to be no parades or reveille. On Christmas Eve half of our squad was on guard duty. We, the other half, had the day off and decided to out for a Christmas Eve drink. We booked out at the guardroom, had a few drinks in the bars of Woking Town, came back to barracks and booked in. It was about 11.30pm. On piquet duty outside the guardroom archway gate was Taffy Watkins. Taffy was the timid one of our squad and as we booked in, one of our group said to Taffy. "Watch out for the ghost at midnight she is supposed to walk the tower every Christmas Eve." As said earlier, the Victorian ex prison buildings that overlooked the square were very gaunt, severe and sombre looking. Usually the only light that shone on to the parade ground, at night, was from the guardroom archway or the illuminated clock on the tower. The tower, meaning the clock tower, was directly facing the archway entrance across the parade ground, about 50 yards (Mtrs) away. We left Taffy on guard, laughing and joking. Arriving at our spider barrack room someone suggested we arrange for the ghost to walk specially for Taffy. We discussed the operation with what we thought military precision. Four of us got a white bed sheet and a candle. We congregated in the passageway under the clock tower. I placed the sheet over my head and I held a lighted candle under it. On the stroke of midnight I exited the tower on to the parade ground. I slowly walked around the tower heading for the other doorway. Taffy adjacent to the square wasn't looking in our direction. I hissed to my mates to make a distraction. One banged a door. It rang loudly around the square. I carried on with my walk. Taffy looked over in my direction and seeing the apparition let out a howl. I felt the urge to run and get off the square, but I had to contain myself and continued the slow walk to the other exit. As soon as I had done so I raced back to the barrack room. We all undressed laughing and climbed into bed, all lights were extinguished. We were still laughing about the escapade when we heard a commotion outside. It was the Guard Sergeant, we pretended sleep. Because Taffy had claimed to have seen the ghost lady of Inkerman he had let out a yell. The guard Sergeant called out the guard and a search was made around the clock tower. The Sergeant had the suspicion that it was members of our squad that was fooling around. We were the only ones in camp and after all we had only just booked in. He came into our room and turned on the lights. Everyone was ordered out of their beds. Luckily we were all wearing pyjamas. He accused us of playing the fool although he could not prove it. He even threatened to take our pulses to see if any were racing. A fast heartbeat would tend to prove we had been running or up to some mischief. He didn't. He admonished us lightly and with a hint of a smile on his face, left. I have often wondered if I had been given a direct order to tell the truth. Had we had been involved? Would I have confessed? I don't know. The upshot of the tale was that when the other half of the squad was relieved of duty and came back to the barrack room they related the incident. We pretended that it was all news to us. Taffy was convinced he had seen the ghost of Inkerman. We did not enlighten him. We all made a pact of silence. I kept to it. I wonder to this day does he know the truth? Inkerman Barrack was famous for its 'White lady' Ghost. Did we add to the mystery? On Christmas morning we had been instructed to remain in bed. At 9 O Clock the CO., RSM., other officers and senior NCO’s came into the barrack room with an urn of tea and food. The CO served the Tea to us in bed. The RSM offered to lace the tea with whisky. Others handed out Turkey sandwiches, Christmas cake, fruit and nuts. It was rather disconcerting to be in bed with senior officers in the room and I personally was glad when they left. Even the guardroom duties were more relaxed than normal. We were treated quite civilised really. Our Squad began Christmas leave on New Years Eve. During this break I continued to try and convince my wife to accept that the army was to be my future career. She remained negative, insisting throughout that I obtain my discharge by purchase. On return from leave we had entered the military law stage of training. I, not be particularly brainy, was a little apprehensive of it. We had been forewarned of the content and I wondered if I could commit to memory large definitions of offences and the dreaded judges rules. On the First day of Military Law we were given the first judges rule:- 'Whenever a Police officer is endeavouring to discover the author of a crime he may question any person or persons, whether suspect or not, from whom he thinks useful information may be obtained' There were Nine of them and Seven other definitions of offences. Arson. Assault Burglary. Homicide, Murder, Theft and Treason. All had to be learned word perfect. There were numerous other offences in both Common, Statute and Military Law that we had to have a thorough working knowledge of. At that time there were one of three cautions that could be given to a suspect. Each one had to be learned exactly. I had never before had to learn any tract parrot fashion. Before that time I did not know the meaning of the words, parrot fashion. It of course means to learn exactly as taught. Every letter had to be in place, any added or missed, pronounced the definition wrong. We would be required to have a written test every day on the definitions. I was dreading this stage of learning. I now realise that every other person was in the same boat as myself. We had been instructed that all persons react differently to situations and what was ideal for one was not necessary right for another. Everyone learned things differently. That first evening I tried sitting on my bed trying to learn my first tract. As soon as I thought I had learned the first line, I forgot it before I could get the second line off by heart. I was at a loss, this was going to be even harder that I had originally thought. I remembered the instructor had said that his method of learning anything verbatim was to absent himself from everyone and to concentrate, completely alone. I had an idea. I went into the drying room. Few persons went in there, only to take or retrieve drying clothes. I stood completely to attention with the written definition of the first Judges rule in my right hand. I read the first line and, still at attention, repeated it out loud. I repeated it again and again until I felt I had it. I then read the second line and coupled it to the first. Again out loud I repeated them time and again. Anyone who came into the room would look at me, as though I was off my rocker, talking to myself, but having said that they probably understood the urgency of my actions. It began to work for me, within two hours I had the whole tract off exactly. I was jubilant, I had succeeded against all odds. I really felt success, I could do it, I was not thick. All that evening I repeated my new found knowledge to myself, determined that it would not escape me. My last thought before sleep that night was the judges Rule number 1 and the first thing I did on wakening was to repeat it. I was now looking forward to the law phase of my training with new found confidence. I knew it was in my capability to pass this stage. I was still receiving letters from Brenda about how unhappy she was, urging me to take the option of buying myself out of the army. I was completely all at sea with the idea. I just did not know where to turn for the best. I was in love with my wife but it was as if I was committing adultery with the army. On Tuesday the 19th of January I was in my tenth week of training. I had been in the army eleven weeks and two days I reckoned I had while Friday as the last date in which I could apply to the orderly room for a discharge by purchase. I still could not make up my mind I was like an Ostrich with my head in the sand hoping that my problem would go away. I just wanted for next Monday to come and then a decision to buy myself out would not be an option, it would be too late. Although training was hard I could see a golden end to it. More than anything that I had ever wanted was to pass out at the Sixteen week stage. I was in a Military Law class and a runner came into the room with a message, 'The RSM wanted to see Probationer Gale in his office now' What had I done? The RSM only dealt with serious matters. On the way to his office I racked my brains as to where I had gone wrong. I knocked on his door. "Enter" Thundered the RSM On entering, he was seated behind his desk and an officer was sat at his side. "Probationer Gale reporting as ordered sir." I trembled. On seeing the officer at his side, I correctly saluted him. "Stand at ease Gale." said the RSM. "This officer here is Colonel White of the Royal Horse Artillery. He wants to speak to you." I stood properly at ease but my inner body was rigid. The RSM left his office. "Pull up a chair and please sit yourself down." said the Colonel What is going on here I thought. He seems friendly enough perhaps I am not in the doghouse after all. "So you are the fellow who is to come to my riding academy next week? I am here to tell you about the training you are about to undertake." I now realised why I was in this office. The officer was to brief me for the Horse Riding training in preparation for the Pentathlon event I was to be prepared for. Another school would teach me fencing exactly like Lieutenant Mayhew has said. "With respect sir," I interrupted. "there is a chance that I may not remain in the army. I am having marital problems and I may have to buy myself out." "Oh!" he said, obviously surprised. "I was not aware of this." He stood up. "Good-bye Gale" and with that he left the office. I stood up and saluted his hurried departure. A few minutes later the RSM entered. "What do you mean telling a Colonel that you are going to buy yourself out of the Army." He bellowed. "You do not go around talking to Colonels like that." "Sir, I am sorry but there is a chance I may have to do it, and I do not want the army making arrangements for me that I may not be able keep." "Sit down and tell me about it" The RSM’s demeanour changed dramatically. He became like a father talking to a son. Although I could not relax in his presence, at least I managed to get most of my story out. "Can you afford to remain in the army and buy yourself out after your 12 weeks are up?" He asked. My answer was, "No sir, I can manage the Twenty Pounds but certainly not the Two Hundred and Fifty." That is what it would cost at least, even a day after the 12 weeks. He commiserated with my dilemma and said that only I could make the final decision. He understood that I loved my wife and child but that I was also looking for a future in the army. I had now to make a decision. I there and then decided to buy myself out and told him. He rang the orderly room Sergeant and arranged for me to see him. Within 2 hours I was on my way out of the barracks. A discharge by purchase order and a rail warrant in my hand. I felt the most despondent person on earth. Where do I go from here?

Weeks

earlier I had thought, on the train from Leeds to Woking, that I may

have made a mistake in joining the army. Now, on the train from Woking

to Leeds, I was certain I had made a mistake in leaving the army.

Tuesday, late afternoon, I entered my house unexpectedly, to be greeted by my wife and child. Somehow I did not feel the same as when I had come home on the 72 hour pass. I had done all that hard work in training for nothing. I was now back to square one. That night I lay in my wives arms, I knew this was the woman whom I wanted to be with but during the day I wanted something else. That something else was not the pit. I wanted my cake but I also wanted to eat it. Thursday I received a letter from the conscription board, I had been given an appointment for the following week to attend a service medical. I was still eligible for National service. They had been quick off the mark and had not let the grass grow under their feet. Saturday morning I went to see Bennie W., the mine training officer, for a job. As expected, he gave me one. Monday I returned to the pit. I was given a shot firing job but not at staff position. I was promised one at a later date. The pit, the people, the job, were exactly the same but I was not. It was I who had definitely changed. Whereas, prior to the army, I could see only the good things about the pit, then I grew a little older and began to tolerate it, now I hated it. The pit was my prison and I was starting a life sentence. Whenever I related to my mates how hard and different the training was at the RMP Depot I could see doubt creep into their eyes. Were they thinking that it had been too hard for me? That I could not hack it? Nothing could have been further from the truth. I had done the hardest part I had been almost home and dry. That first week I only worked 3 shifts, I had Thursday and Friday off. I just could not take it. I made excuses with illness but the sad fact was that I was feeling wretched and sorry for myself. 'Knocking', or absenteeism was to become a habit with me. I very rarely completed a full 5 shifts in the week. At that time the contract of employment stated that if a person worked the full 5 shifts then he would be granted and paid a sixth bonus shift. I very rarely received bonuses. In later months when I made an appointment to see the manager for a shot firing staff position, he took out my attendance record. Of the 12 weeks since I had been back I had only completed one whole week. He promised to review my case in 3 months and if my attendance record improved he would reinstate me to staff. Inwardly I knew there was little chance of that happening Peter W. I later learned successfully completed RMP training and was posted to Berlin. I remember him coming home on his embarkation leave, resplendent in his uniform. Very rarely have I been envious of another but I remember being so when I saw him. I pretended non -chalance but my mind churned green with envy. Three weeks after my discharge Walter T., the NACOD'S Union representative, said to me, "Why not join the TA" Walter was the one who had originally recommended the RMP to me. I had heard of the Territorial Army but did not know much about it. He explained that persons who joined the TA were interested in the Armed Services but held civilian jobs. It was an army held in reserve. They were nicknamed 'Saturday Soldiers' He furthered that there was a TA Camp up at Oakwood Barrack, Roundhay, Leeds. "They have Redcaps up there too." My ears pricked up when he said "Redcaps". I did not know there were Military Police TA. Although having thought about it there must be. The news sounded good. That evening I found the telephone number of Oakwood barracks and rang them to enquire. "Yes they were the RMP TA and they had vacancies. Just turn up any Tuesday or Thursday between 7 and 9 PM. They would fix me up." The first Tuesday I arrived and enrolled with the 49th Infantry Division of the Royal Military Police. Territorial Army. 49 Inf. Div. RMP. TA. for short. I thoroughly enjoyed my first evening. Everyone, officers, NCO’s and others were very friendly. I could not wait for the next drill evening on Thursday. I had expected the discipline to be pretty much the same as at the Depot in Woking. I could not have been farther from the truth. The weekday drill nights involved 2 hours of training. It varied from lectures to drill square periods or the preparation of kit for a coming weekend. Promptly at 9 O clock we were dismissed and the unit bar was opened. We usually drank until 11 That second evening I enquired of an NCO "How long does it take for a new recruit to pass out?" I got the reply. "When he's had too much to drink." I now had a new interest in life. Slowly but surely the TA began to mean more to me than just a hobby. I again felt the feelings of belonging to something important. My married life and employment were something quite apart from the TA. I would not have liked anyone to make me chose one or the other. I had already made a similar choice and regretted it.

"Do you know the muffin

man,

the Muffin Man, the Muffin Man. Do you know the Muffin Man who lives in County Clare."

At that time I had a Heinkel 3

wheeler, the controls of which were similar to a car. Because it had

the reverse blanked off and only had 3 wheels it could be driven on my

motor cycle licence. I thereby graduated from Motor Cycle hand controls

to car foot control.